Walk,

Don't Walk,

Dont Walk

Examining how good design conveys messages through pedestrian signals

Automobiles transformed city streets around the world. For most of human history, streets were built first and foremost for people on foot. The traffic on these city streets consisted of crowds of individuals today better known as pedestrians now. These people walked to and fro wherever they wanted. It was true freedom.

As cities grew in density, streets became messy. The chaos of foot traffic gave way to horse drawn carts and carriages. Horse manure was a huge nuisance. In the 1880s, New York City horses were producing 100,000 tons of manure a year and 10 million gallons of urine. The streets were a mess, and so unsurprisingly, it was also the 19th Century that saw a big expansion of sidewalks. Sidewalks typically had been a luxury built to serve limited locations before then, but segregating people from horses became necessary as streets became increasingly crowded.

Detroit Publishing Co., Publisher. Horse-Drawn Street Car. United States Michigan Detroit, None. [Between 1915 and 1925] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016816971/.

The car changed everything. Even as city leaders worried about how to keep the streets clean, mass production of the automobile quickly reduced the demand for horses. Simultaneously, electric streetcars also replaced horse-drawn omnibuses as well. By 1912, cars outnumbered horses in New York City, and the manure emergency started to wane.

The cars created a new crisis – they proved a dangerous addition to urban streets and by the 1920s, as many as 250,000 people, many of them children, had been run over by cars. Something needed to be done.

To solve the problem, Americans invented jaywalking. Advocates wanted to stop pedestrian deaths, but in so doing, criminalized the act of walking. The term "jay," then a pejorative referring to a yokel unfamiliar with more sophisticated etiquette, was at first applied to drivers. Jay drivers referred to people who didn't know how to operate their vehicles.

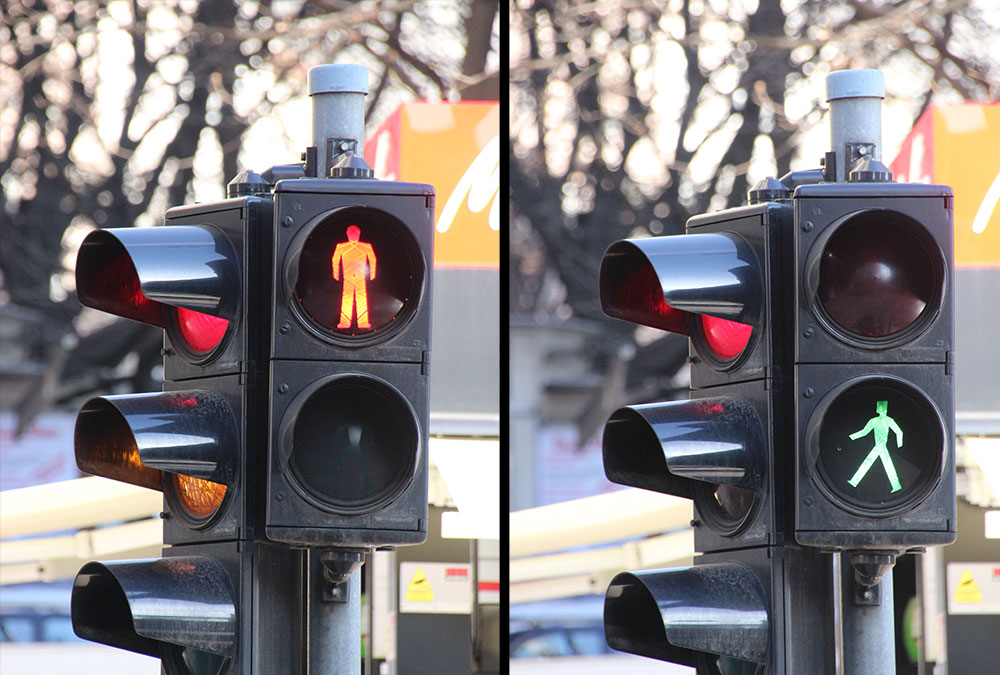

Walk and don't walk signals in Belgrade, Serbia

But Americans love cars, and so naturally limiting pedestrians proved easier than restricting cars. The first law requiring people to cross as designated places was passed in Kansas in 1912, the same year cars outnumbered horses back in New York. Other cities followed. Los Angeles, also an early adopter of zoning laws, created some of the strictest pedestrian laws passed by 1925. Suddenly, it was the pedestrians who were jaywalking rather than car owners jay driving.

In the 1920s, electric traffic signals became popular urban features in cities around the world. They became so important, Western nations held a literal Geneva convention in 1931 to standardize the signals and road signs. Subsequent conventions have maintained the standards recognizable today, and although the United States conforms to their own set of rules, many of these are universal symbols, such as the red octagon "stop" sign and the green, amber, red traffic light.

P of course, are not cars. People walking around the city needed their own signals. In New York City, the first of these pedestrian signals are thought to have been installed in the 1930s. Former police officer Dr. John Harriss is credited with one awkward design for midtown Manhattan that involved the palm of a hand and circles of green and orange lights. It wasn't in widespread use.

"Walk"and "Don't Walk" signs debuted in Washington D.C. in 1939 with New York City installing pedestrian signals with "Walk" and "Dont Walk" in 1952. The orange and white colors were also a new feature. New York's don't walk signs also famously leave off the apostrophe, one of the reasons New York Magazine loves New York in 1976.

The New York signals became so iconic, the artist George Segal produced a sculpture, Walk, Don't Walk, in 1976, now housed in the Whitney Museum of American Art. It features three people standing alongside a pedestrian signal on a street corner.

However, by the early 2000s, New York City's Transportation Department began replacing the old signs with more energy efficient models. And during the phased in replacement program, they swapped out words for symbols. New York's signal boxes have an orange hand to indicate "stop" while a white-lit man posed in a walking motion indicates pedestrians have the right of way. Contemporary signals also have clocks counting down the remaining time.

Despite the many pedestrian signs, New Yorkers are far less likely to wait for the traffic signal than pedestrians in other places. We simply don't have time to wait. In my experience, countries with previously fascist governments are much more likely to wait at traffic signals than democracies with a history of freedom and liberty.

A female figure in Netherlands serves as a walk symbol

Pedestrian signals remain unique around the world. Despite standards for stop signs and no parking signs and dangerous bend signs, countries and even sometimes cities have their own unique imagery for "walk" and "don't walk."

Most signals include representations of men for both walk signs, one with a man standing at attention and the other where the man shows motion. There are a few exceptions, such as a depiction of a young woman in some Benelux countries or depictions of both mean and women together. Some characters have accessories like hats or walking sticks. Others share local history, like a Danish crossing signal depicting 19th century soldiers to commemorate a 1849 battle.

These symbols communicate the same message, and while each is unique in smaller ways, they mostly share common traits. The don't walk symbol in most places features a character that is standing still. How is the lack of motion depicted? Usually the character's legs are close together, side by side, and symmetrical. By contrast, the walking figures have legs that are spread apart, asymmetrical, and of different lengths, imitating the motion of walking. Even with accessories like hats and skirts and bicycles, the walk / don't walk characters have enough common features to provide universal understanding.

The great outlier is the American upraised hand indicating don't walk. The American walk signal of a jaunty looking man hunched forward ready to launch at the start of a sprint shares the same common traits of walk signals around the world. But the upraised hand is unlike any other.

The symbol is a command. It doesn't demonstrate the action, but orders it. While a standing figure shows pedestrians how they should act, the hand tells them how they should act.

But from a design perspective, the hand conveys a clear message: stop. It is well known and widely used, even before the hand symbol was installed on street corners around the country. Police directing traffic use the open hand to indicate vehicles should stop when directing traffic. Or consider The Supremes singing "Stop In The Name of Love." When the singers dance, they hold up their hands on "stop," in the same motion as the upraised hand of the crossing signals.

Figures in Japan wear hats on the walk and don't walk symbols; the don't walk symbol needs the walk symbol to contextualize meaning.

The symbol of the upraised hand is well known even outside the United States and conveys the critical information through design: stop. It even conveys this message independently of the symbol for walk, unlike pedestrian signals in Europe. A standing figure depends on the walking figure to provide meaning, to create the context to understand that the standing figure is the opposite of walking. The symbols work in tandem, but alone lose meaning when separated. Without the walking figure, the standing figure is just an illuminated man standing around.

The design of both styles of crossing signals conveys the message. The subtle differences in each design also conveys meaning about the culture. Including a female figure demonstrates a commitment to gender equality. The use of a hat suggests a formality in the culture. The commanding hand of the American don't walk symbol indicates our relationship with authority – and our willingness to jaywalk a uniquely American rejection of that authority. Even the missing apostrophe from New York City's "dont walk" signs point to the city's fast pace culture; we don't have time for apostrophes. Everywhere we look design is being employed to convey information.

Additional Citations

Richard F. Weingroff, "On The Right Side of the Road," Federal Highway Administration

Kurt Kohlstedy, "The Big Crapple: NYC Transit Pollution From Horse Manure to Horseless Carraiges," 99 Percent Invisible

Avi Selk, "The Death of teh Sidewalk", The Washingto Post

Joseph Stromberg, "The forgotten history of how automakers invented the crime of "jaywalking"", Vox

Ravi Mangla, "The secret history of jaywalking: The disturbing reason it was outlawed — and why we should lift the ban," Salon>

"'Walk' and 'Don't Walk' Signs to Be Tried In Signal Color Variations for Pedestrians,"" New York Time

Ed Boland, Jr., "F.Y.I.," New York Times